The ancient Egyptians built their pyramids themselves.

Scientific evidence backs it up.

We, travelers of the 21ᵉ century, arrive with our beliefs and prejudices before the immense Egyptian civilization. We are bewildered by marvels that are so beyond our comprehension that we have difficulty understanding them. Some people have allowed themselves the right to call history into question in the light of their imaginations, or even their delusions - or worse: their personal interests.They forget the historical and scientific evidence, obtained through hard work. They want to make their fictitious assertions coincide with history.

Historical evidence is recognized and validated by all historians and scientists, such as carbon-14 dating studies, and offer us the right path to follow. Artifacts, texts and paintings found on dig sites provide elements allowing research and translation, leading to evidence that is universally accepted. State-run institutes such as the Cairo-based IFAO (Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale) publish scientific works that are unanimously acclaimed by the scientific and academic world.

Studying Egyptology takes time. Some people are reluctant to take on such time-consuming work, forcing them to contradict their own imaginations. In archaeology, obtaining even one piece of irrefutable evidence is a challenge, but it does enable us to demonstrate facts that were incontrovertible at the time of their discovery.

Here are four such proofs we can study:

1 - The Wadi el-Jarf papyri

Very recent discoveries of vital importance have been made on the shores of the Red Sea in the course of a joint expedition by Cairo-based IFAO, the Sorbonne University and the University of Asyut. Since 2011, Pierre Tallet of Sorbonne University has been leading these excavations and continues to work on the sites.The Wadi al-Jarf site lies on the western coast of the Gulf of Suez, 23 kilometers from the town of Zafarana, at the foot of the monastery of Saint-Paul, in the Egyptian desert.

Galleries were used to house and store equipment, as well as boats to get to the copper mines on the other side of the Red Sea. They were installed in the shape of comb teeth, where boats could be dismantled and stored for later use. Pierre Tallet has unearthed 800 papyrus fragments on this site. These are large documentary deposits found in the closing systems of galleries G1 and G2 on the site, a daily accounting journal that reported on all the work carried out by Inspector Merer's teams (former empire). His teams, or 'phylés, had their own names. One was called “The Great”'. Merer was not the only inspector; Inspector Dedi carried out the same tasks with similar teams bearing other names.

Inspector Merer, to whom the majority of the documents found belong, recorded on his papyri every evening, for months on end, the transport of stones from the limestone quarries of Toura North and Toura South. These stones were destined to clad the Great Pyramid of Cheops on the Giza Plateau.

The nummulitic limestone, on the other hand, was destined for the pyramid's internal filling. These stones were not cut, but rough. Sometimes the Egyptians used a kind of mortar to fill the spaces between the stones, and this can still be seen on site today. The upper chamber of the Cheops pyramid was built from Aswan granite.

Here's a translation of a papyrus passage (a true transcription of the ancient Egyptian language specific to the Old Kingdom.

Day 21: Inspector Merer spends the day with his phyle 'team' loading a transport boat at Toura North; embark from Toura in the afternoon.

Day 22: Spend the night in Ro-Ché Khoufou'. In the morning, embark from Ro-Ché Khoufou; sail to Akhet Khoufou; spend the night at the Chapelles d'Alkhet Khoufou.

Day 23: the director of the 10ᵉ Hesi spends the day with his naval section in Ro-Ché Khoufou, because it has been decided that he will sail; spend the night in Ro-Ché Khoufou.

Day 24: Inspector Merer spends the day with his phylé, hauling in the stones for the boats with the people from the elite role, the âper teams and the noble Ankhaef, director of Ro-Ché Khoufou.

Day 25: Inspector Merer spends the day with his team hauling stones in Toura, spending the night in Toura Nord etc.

Transfer by river to the royal construction site of the pyramid known as 'akhet Khoufou' (Khufu's horizon).

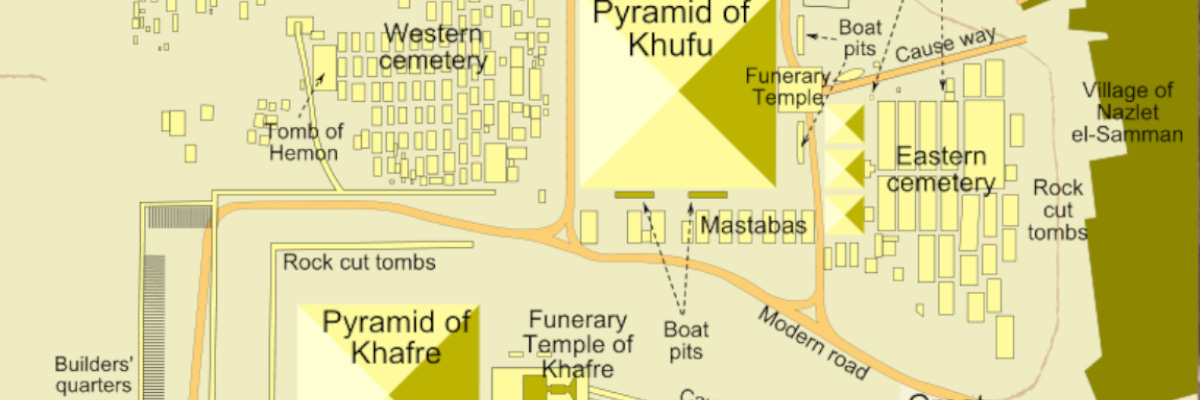

The entire construction site consisted of several elements:

the pyramid

the high temple

the rising causeway

the lower temple or valley temple

A landing stage has been discovered, used for unloading boats from a central basin called 'she khoufou' (Lake Khufu). On the landing stage were chapels and an administrative center named 'ankhou Khoufou', which translates as "long live Khufu". The boats rotated at a brisk pace, almost every day and a half, to cover the distance from Toura to Giza, some 40 km round trip.

Inspector Merer also exploited the copper and turquoise mines on the opposite shore of Wadi al-Jarf.

Copper was arguably Egypt's most strategic resource, used for weapons as well as the tools needed to make the chisels used to cut stones. It was also used by craftsmen to carve certain statues in sandstone or limestone, as well as for the blades and saws needed to make the stones used in buildings.

The mines were located on the Wadi al-Jarf road in the eastern Wadi Araba desert. They obtained copper by oxidation-reduction of the copper ore malachite, a chemical process that produces metallic copper by combustion. Furnaces have been found both on the copper mines opposite Wadi al-Jarf and on the Giza plateau, where alignments have been unearthed. Turquoise in particular was found on the opposite bank to Wadi al-Jarf.

The quantity of copper has not been recorded, but it seems that a very large quantity of copper was required, as it wore out very quickly. The price of copper was exorbitant, and required quasi-industrial facilities to keep up with the galloping demand for the metal.

These are recent discoveries, but of the utmost importance, in that they undeniably prove that the stones were indeed transported from the quarries to the port of Cheops to be used in the construction of the pyramid. Excavations at the Wadi al-Jarf site, directed by Professor Pierre Tallet, continue unabated.

2 - Previous discoveries on the Giza Plateau

In May 1837, British archaeologist Howard Vyse uncovered the discharge chambers above the King's Chamber in the Pyramid of Cheops. He discovered graffiti painted in red ink by quarrymen, who inscribed the names of their teams, the Phylées. These names could be as classic as 'Khufu's followers' or as strange as 'Khufu's drunkards'. This red ink was usually used in quarries. It was produced by crushing red stones found in the desert, obtaining a kind of powder which was then mixed with oil.

These graffiti prove that this pyramid belonged to Pharaoh Khufu 4th dynasty, his name is clearly written inside a cartouche (khoufou) followed by the name of the Phylea, and that it was assembled by teams of specialized workers.

3 -The discovery of the installations south of the Wall of the Crow

To the south of the Wall of the Crow, Dr Zahi Hawass and Dr Mark Lehner discovered the tombs of the foremen and workers who built the pyramids. Those of the foremen were quite elaborate, with a corridor decorated with paintings and texts giving the name of the owner. There are also references to the protection of the tomb, such as curses against those who would dare to desecrate the site. These include columns of ferocious animals such as lions, crocodiles, hippos and snakes, ready to devour them. At the end of the corridor, a descenderie, or burial shaft, contained the coffin of the mummified deceased.

Workers' tombs were simpler, consisting of an excavation in the ground with the remains of the deceased. Sometimes, a piece of pottery, cloth or animal skin would cover the desert-mummified body. The main interest of these tombs is to prove that the pyramids were not built by slaves.

Dr. Mark Lehner found the entire area containing the living quarters of the workers and foremen. The remains of bakeries and ovens for cooking meals were uncovered. They were all very well-fed, so that they had the strength to work hard. They enjoyed hearty meals of beef, duck, goose and fish, as well as bread, onions, garlic, lettuce, leeks, broad beans, walnuts, grapes, honey cakes, beer, and Nile water.

Dr Mark Lehner also found the remains of resting places where several workers lay down to sleep, protected by a roof made of palm leaves. What's more, he also discovered places where meals were taken under arbors shaded by palm leaves.

A quasi-military organization was put in place, and all regions of Egypt participated by sending meat, fish, vegetables, fruit, wheat for bread, honey and beer, among other things.

All this organization contributed to the extraordinary end result of the Cheops pyramid, which we believe must have taken 20 or 25 years to build.

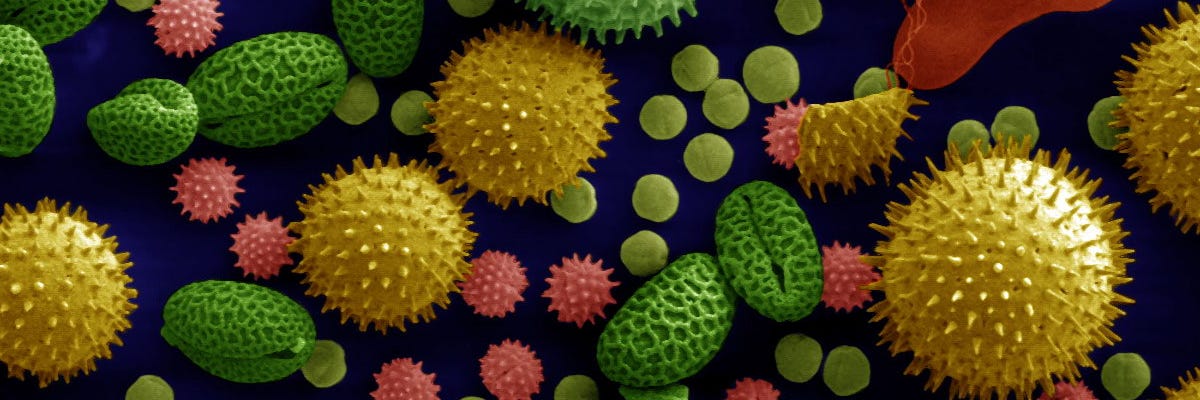

4 - Francine Darmon's work on Kheops pollens

Pollens, the male reproductive elements of flowering plants, are the true witnesses of plant life preserved in sediments, enabling us to reconstruct elements of the past. Pollens were found in the interstices of the stone joints in the corridor leading to the Queen's Chamber, the pyramid's middle corridor. Other legume pollens were found in large quantities (almost 2,000 per slide), attesting to the fact that these materials were located in the immediate vicinity of cultivated surfaces, as well as myrtle and water lily (nennefer) pollens.

A smaller percentage of aquatic pollens were found, indicating the contribution of the Nile in the manufacture of mortar for stone joints. Papyrus and willow pollens were also found in the vicinity of the pyramid.

The Egyptian pyramids were indeed built by the ancient Egyptians, who had all the technical means at their disposal, but above all their practical sense.

Culture

Finally, so-called extraterrestrials would not have interfered with a construction of great religious value. They would not have been concerned with this aspect, and would have deprived the Egyptians of their opportunity to access the afterlife they had earned through their work. Working for the pharaoh was considered divine service.

Translated from French by Guillaume Fournier Airaud

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0